The sustainable development of a single country, Brazil, in 2021 is an effort incubated in globalization’s cauldron of interdependent systems. The defining events of the beginning of the 21st century have all been exacerbated by a historic chain reaction of interrelated multi-generational consequences. The implications for how emerging industries and economies in middle- and lower-income countries can compete domestically and globally in this complicated ecosystem are significant. For example, the financial crisis of 2008 has revealed that our financial systems are intertwined so much internationally that a global housing crisis in the US or China will impede access to capital that the Global South’s development efforts require[1]. Covid-19’s rapid yet lasting impact in just two years underscores the need for a coordinated system-wide set of solutions to address these types of all-encompassing problems. Climate change’s slow but steady impact follows no boundaries and now requires a system-wide global response across markets, industries, and countries to abate further temperature increase and the resulting negative consequences. This paper touches upon several environmental-related policy responses across industries to present that a holistic coordination of this collective effort is necessary.[2] The following is an analysis of how, before climate change become the world’s pressing disaster, Brazil addressed different climate change-related challenges across strategic economic development-related systems and respective sectors: policymaking, environmental, foreign direct investment, and energy.

Brazil is part of the rapidly growing Global South and one of the BRICS. Governments experiencing faster economic growth are faced with sharper trade-offs when deciding how they steward their economies and design environmentally sound development policies across sectors. Popular public sentiment in a properly functioning market democracy does influence policymaking. A study that explains why environmental awareness is so high in Brazil, confirms that their environmentally friendly public is largely attributed to having an electorate with higher levels of education, no other socioeconomic characteristic has a stronger regression coefficient.[3] Does a Brazilian education confer any special focus on environmentalism? Or is the long-term nature and complicated science behind climate change so vast that it does require understanding a combination of advanced topics in economics, math, statistics, public policy, earth science, energy, and agriculture to be convinced that climate change is an urgent problem that requires an international government-led response. Unfortunately, the following course of events shows an environmentally friendly public isn’t sufficient for Brazil to “stay the green course”. Nonetheless, this finding bears an important political facet about Brazil, it has an electorate that has long supported environmentalism[4]. While this is only a single factor and doesn’t explain Brazil’s long history of environmentally-focused public policy decision-making, different trends have emerged among the BRICS which have developed more or less responsibly.[5]

Emerging democratic market economy policymakers who sustainably develop a country’s resources to continue its economic growth benefit from influential political factors like the public’s support for long-term sustainable economic development. Environmental considerations pervade across important development policy decisions like how an economy produces a critical factor of production: electricity. Since the 1970’s Brazil’s largest single energy production source has been hydroelectric energy generation and currently stands at 70% of their electrical generation.[6] The development of hydroelectric dams requires suitable rivers to reliably generate energy. Though Brazil is home to noteworthy river systems, a 2015 comprehensive review of the global potential for hydro-generated electricity ascribes a greater potential to Russia (2401, ranked #1), China (2329, ranked #2), and India (387, ranked #9) than to Brazil, 319 (ranked #12)[7]. Indicating that Russia, China, and India all have the natural resources to add more renewable production than is currently built in their respective countries when compared to Brazil’s installed base of hydroelectric dams.

Instead during the same period these three BRICS countries developed coal-based electricity generation. Coal-fueled energy production increased in Russia by 45% from 7.25 quadrillion BTUs (quad BTUs) in 2008 to 10.51 quad BTUs in 2019 to compose 16% of their energy portfolio. Coal-fueled energy production increased in India by 35% from 8.10 quad BTUs in 2008 to 10.94 quad BTUs in 2019 to compose 64% of their energy portfolio. And in China coal-fueled energy production increased by 37% from 64.66 quad BTUs in 2008 to 88.44 quad BTUs in 2019 to compose 71% of their energy portfolio. Coal-fueled energy production increased in South Africa by .4% from 5.54 quadrillion BTUs (quad BTUs) in 2008 to 5.56 quad BTUs in 2019 to compose 95% of their energy portfolio. Meanwhile Brazil decreased its coal-fueled energy production by 14% to .09 quadrillion BTUs which composes 1% of their energy portfolio.6

As of 2016, there also were Brazilian states like Minas Gerais with lower hydroelectric production proportions and where hydroelectric power generation had “almost been exploited to its maximum [and was] highly vulnerable to droughts, such as the ones the state [was] experiencing. Due to the lack of precipitation and investment in the sector, the use of power plants based on fossil fuels increased considerably” leading up to 2016.[8] As of 2008, before the world reacted more urgently to climate change, 50% of Brazil’s consumed electricity did not depend on fossil fuels. Then in that same year Brazil discovered over 8 billion barrels in a new oil field which may change its status to become a significant global oil exporter[9]. While this hasn’t come to pass yet, since the 2008 discovery of the Tupi fields, Brazil’s daily petroleum production in 2019 has grown by 1,337 thousand barrels a day (Mb/d); more than the daily increases in Russia (+685 Mb/d) and China (+621 Mb/d) combined.[10] During the same period, Brazil’s renewable portion of its energy consumed decreased from 50% in 2008 to 44% in 2019. Brazil’s energy consumption trend is less environmentally sound than its renewable-laden energy production capacity. Even so, Brazil’s overall annual production of fossil fuels dependent energy is still only 56% percent of its total production while Russia (94%), India (80%), China (83%), South Africa (96%) are much higher.7

The negative consequences of pursuing dirty energy development have already been measured in Russia, India, China, and South Africa by the World Economic Forum.[11] “BRICS countries have largely upheld policies to ensure affordability of energy to drive competitiveness in industry. Industry growth has been the primary driver of energy demand in countries like China, where industry accounted for nearly 50% of final energy consumption in 2012. These policies have, to some extent, been to the detriment of the environmental sustainability of the energy systems that developed as a consequence. In response to growing environmental concerns, both China and India have set a range of targets to reduce the energy intensity of their economies and improve their climate metrics.”[12] Much of Brazil’s electricity is supplied through hydroelectric production. However, dam building in Brazil is not an ideal single solution for producing energy since it has negative consequences for indigenous people and the environment.[13] This quick comparison of the BRIC’s different energy production and consumption trajectories highlights the different repercussions on their climate change policy options. While Brazil is growing its oil production and compromising its environmental leadership the rest of the BRICS are trying to clean up after themselves and reform their energy sectors.[14]

Energy production and energy policy is a feedback loop to help direct the development of Brazil’s society, infrastructure, and economy to face the challenges of climate change. Stakeholders are challenged to react to these feedback loops with scientific and policy research which is locally and globally salient, ensures participation of key stakeholders during the entire research cycle, communicates understandable results to disparate audiences, and builds a political constituency for policy changes.[15] The following stakeholders have already been identified concerning the energy policy issues explored thus far: NGOs representing different public interest groups like scores of indigenous groups, the environment, fisheries, national defense departments that protect natural resources, energy companies that develop deep-sea oil wells, environmental gatekeepers that assess the impact of energy projects, the energy-consuming general public, energy industry investors, government energy regulators, public sector efforts to educate the public, management of public services affected by oil development (beaches, marine recreation, etc), and environmental research efforts focused on that locale.

That long list reflects that many actors will be required to produce effective policy research. A case study on international environmental NGOs and conservation science and policy in Brazil determined that “scholars have found that for science to move policy there must be work across boundaries (Jasanoff 1987), defined as the “socially constructed and negotiated borders between science and policy, between disciplines, across nations, and across multiple levels. […] One way of spanning the science-policy boundary is through boundary organizations. Boundary organizations’ most critical attributes include accountability to and enabling [the] participation of actors on all sides of the boundary (Cash 2001; Clark et al. 2002), serving to create and utilize linkages that connect scientists to managers and policymakers through formal and informal processes at multiple scales.”[16]

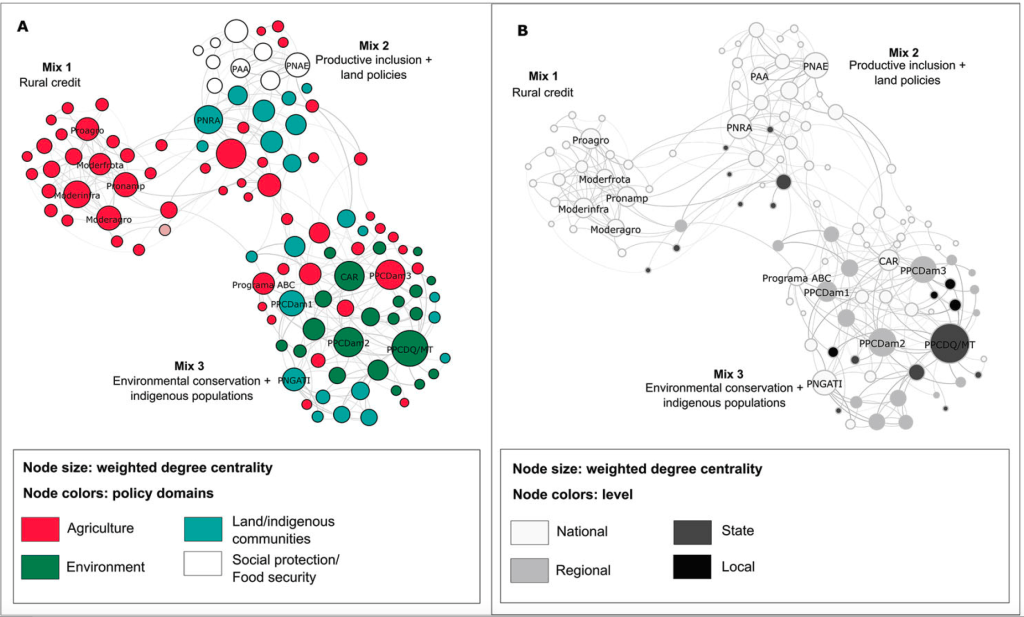

A logical extension of this research finding is that forming boundary organizations could become a regular facet of successful policy development research. This logic particularly supports this paper’s focus on how coordination and synergy between the effort to produce individual policies which reform one facet of the climate change problem are essential for a set of policies to effectively combat climate change in a country. Adelle & Russel (2013) establish this specifically in the example of climate change: “the causes and vectors of climate change and adaptation are embedded across a number of policy sectors (e.g. agriculture, energy, water, and industry), each of which is underpinned by different priorities and involves distinct sets of actors with varying interests. […] Governments rarely address policy goals through a single policy instrument; instead, policy mixes consisting of multiple goals and instruments tend to emerge (del Rio & Howlett, 2013). Responding to climate and land use challenges requires combinations of ‘policy mixes’ that meet policy goals in a complementary manner (Ring & Barton, 2015).”[17] While constructing a complete stakeholder analysis across all of the policy areas addressed in this paper is beyond the paper’s scope, the following graphic exemplifies how the agricultural land use policy considered by Hastings reflects the climate change legislation in Mato Grosso.

The “figure provides a picture of intra- and cross-sectorial interactions among the instruments implemented in Mato Grosso (2013–2017). In Figure a, three main policy mixes are identified using the modularity measure (resolution = 2.0): (i) one rather dense subgroup of agricultural programmes poorly connected with other sectors (mix 1), and (ii) two relatively dense subgroups – or clusters – with a greater number of cross-sectorial interactions (mixes 2 and 3). The first of these subgroups illustrates instruments that promote sustainable production systems, environmental conservation, and the regularisation of indigenous lands (mix 2), while the second subgroup presents instruments of productive inclusion, food and nutritional security, social assistance, and land regularisation (mix 3). In Figure b, it is possible to observe the levels of governance of the instruments inventoried in each mix. For instance, besides being strictly sectorial, mix 1 is almost entirely formed of national instruments, while mix 3 is formed of national, regional, state, and local instruments. The latter illustrates a more multilevel governance pattern.”[18]Hastings’s analysis of this policy area concludes that its strikingly sectoral policy implementation approach impedes this policy’s probable success. This implementation counters the author’s central argument since policy seems to be driven by national-level organizational actors, and shows low connectivity in terms of spaces of coordination. More specifically Hastings supports this claim by citing several Bolsonaro administration decisions and that in this case, central or “State actors often play a dominant role by retaining ultimate control over critical environmental resources, even when they apparently transfer power to other groups and levels of decision making or when they are objects of elite capture.”[19]This latter point is made unfortunately more relevant given the persistent prevalence of corruption in Brazil at the federal level.[20] A pivotal area of economic development policy is the encouragement of foreign direct investment (FDI).

FDI is a required input for the growth of economic sectors in lower-middle-income economies. An Indian government-supported longitudinal econometric study of BRICS countries confirmed a causal relationship between FDI and long-term economic growth. More specifically, “In the short-run, the variables foreign direct investment (FDI), Gross Capital Formation (GCF), trade openness (TO) and real effective exchange rates (REER) are found positive and statistically significant. […] The results of the study [indicate that an] increase in FDI in BRICS countries, [leads to] higher economic growth due to more openness in trade. The results of Wijeweera et al. (2010) and Prabhakar et al. supports results that FDI inflows have a positive impact on economic growth only when accompanied by high skilled labor” in the hosting country. [21] FDI was a core component analyzed in a 2020 study of the role of public-private partnerships (PPP) investment in energy and technological innovations in driving climate change. “PPP is [a] form of collaboration on specific projects among governments, non-profit organizations, and profit enterprises to attain a more promising outcome than anticipated by acting alone.”[22] This model of collaboration is in line with the function of the boundary organizations that Hastings wrote about.

This approach also runs counter to the sectoral policy implementation in Mato Grosso that Hastings criticized. “In Brazil, PPP covers a wide range of projects, such as energy, municipal administration, transportation, and environmental protection. Brazil has one of the largest markets in the PPP in Latin America, having invested around $203 billion in the energy sector from 1984 to 2018 (WDI 2019). [Given the] increasingly evident [impact] of climate change and energy transition from the use of fossil fuels to renewable energy [it] is essential for sustainable development (Gielen et al. 2019; York and Bell 2019).”[23] A finding of this study was that although foreign direct investment increases carbon emissions, to overcome this “issue, the government should improve the regulations regarding carbon emission intensity, set a threshold of carbon emissions to foreign companies and put an end to the entrance of FDI with high energy consumption and pollution.” Any environmentally-leaning financial policy should seek to attract FDI that furthers “research and development for environment friendly technologies, especially for the production of renewable energy.”[24] Though it is out of step with this research paper’s contention, this study also argues for the development of “technologies for clean development and utilization of coal energy”[25]. Thus for a middle-income country, the emerging market-based argument in the course of developing a case for a system-wide response across markets and industries to more effectively grow an economy and abate climate change-related temperature increases and their resulting negative socio-economic consequences may begin with an economic policy focused on climate-change cognizant FDI induced economic growth.

Thus far this paper has compared how each of the BRICS has balanced their economic growth and composition of their energy portfolios as their economies have grown. This has revealed that Brazil is comparatively the most environmentally conscious of this influential group of emerging economies. Brazil’s more recent track record for developing its fossil fuel-based energy deserves a closer examination to understand the social, environmental, and political decisions it has made in developing its energy sector. Research into energy production investments and economic growth has yielded different positive, negative, or non-correlated relationships in different countries. A study by Marco Mele of the bidirectional Granger relationship between real GDP and energy use in Brazil has confirmed “a positive correlation exists between the two variables, which indicate that an increase in energy usage has a subsequent increase in real GDP in Brazil”[26] This scientifically justifies that Brazil, to grow economically should continue to develop its energy production.

Mele further concludes that “it is recommended that Brazil adopts a dual strategy that will improve both the economy and energy efficiency. Balancing the growth of both these variables is an indicator of sustainable growth that enhances the country’s development goals. Policies to promote energy conservation should also be created to enhance the management of pollution in the country. Such policies will reduce energy wastage and generally increase profitability in each unit of energy consumed in a household or industry in Brazil. Investment in energy policies will, therefore, increase energy efficacy and real GDP.”[27] The balance that is stipulated here is of critical importance and is reflected when Mele’s specifies that “investment in energy infrastructure is also a viable strategy to increase energy efficiency (Geller 2012).”[28] His point reflects that as estimated by McKinsey & Company, Brazil’s energy infrastructure losses are 18% of its produced energy while in transit from where it’s generated to its consumption location.[29] McKinsey also identifies that the energy efficiency of important energy-intense economic sectors, namely mining, chemicals, and steel should also be improved.

Usman, Iortile, and Ike 2019 go into a deeper analysis of the historical relationship between economic growth and energy development in Brazil. [30] In the study Usman, et al identified a sequential pattern from 1971 to 2014 that confirmed, in the long run, there is a one-way causal direction between the measures of an ecological footprint, democracy, globalization, and economic growth. The study identified different historical or event-related milestones in Brazil that aligned with the patterns of breaks in each of the measures. During the period, the study’s analysis affirmed that all four variables were positively correlated. Further tests also demonstrated that simulated increases in a preceding variable led to an appropriate positive response in a subsequent metric. More specifically, that over time a 1% higher ecological footprint preceded a .465% increase in measures of democracy, and that a 1% increase in globalization, led to .489% economic growth. Usman, et al contextualize their analysis with other preceding studies that have confirmed the same type of correlations and causation between measures of the same aspects of political-economic development. [31]An important caveat about this analysis is that each country’s development path is different and that another country might also report significantly correlated patterns in these facets of their growth trajectory but in a different sequence. However, in the case of Brazil, this particular pattern is supported by the preceding Mele study findings.

All four variables were then confirmed via a different test (Granger causality tests through the VECM) to have a one-way causal link that ties them all together. Within specified lag intervals between each variable, the positive relationship was strong enough to pass statistical tests for significance. This test validated that forecasts between variables could explain more variance between one metric to the next. It should not be a surprise that these results indicate that “policies that are initiated to preserve the environment may have serious economic implications [yet Usman, et al rightly contend that the real problem is to] focus on ecologically sustainable methods of electricity generation to decouple electricity consumption from the ecological footprint. [… They] specifically suggest that efforts should be made towards increasing the utilisation of the available hydroelectricity power generation in Brazil, seeing

that this is the most ecologically sustainable route. [They also contend] that measures should be taken to utilise other cleaner energy forms, such as wind, solar, and nuclear power, which may have a lower burden on the ecosystem to generate electricity. [Lastly, they also recommend a well enforced] carbon tax levied on individual investors, firms, and industries [that] should not be too large as to discourage investments, [and that] investors should be given a chance to participate in the design of such taxation.”[32] This multifaceted list of policy recommendations is in line with Milhorance’s idea of a set of interrelated policies which should be designed to support each other in the common goal of addressing climate change across different facets of an economy. A continued exploration of Brazil’s energy sector reveals a more detailed understanding of how it evolved.

Flavio Lira provides a historical background and a review up to 2015 of Brazil’s energy industry that helps to fill in and explain how it developed. Among the more illuminating aspects of Lira’s case study is his emphasis on the inconsistent and incomplete nature of Brazil’s oil and gas midstream processing and refinement facilities since Lira contends that Brazil could be more than energy independent and actually become a leading energy exporter. He points out Brazil is not “self-sufficient in oil and gas (O&G) [nor] being a regional geopolitical leader through, among other things, regional energy integration. […Lira summaries that] Brazil has relied heavily on renewable energy and the share of the latter relative to its domestic energy supply has historically exceeded 40 percent due to abundant renewable resources, few relevant coal deposits and a relative difficulty in reaching its natural gas and oil supplies, mostly offshore, which started to change in the 1970s.”[33] Lira also makes clear that “energy independence through state planning, particularly during the country’s last civil-military dictatorship (1964-1985), [when] large hydroelectric projects […became] commonplace in Brazil. […] The northern region, home to most of the Brazilian Amazon, holds the largest hydroelectric potential in the country but, as of 2015, represented only 15 percent of all installed generating capacity” [34].

Lira points out that “diesel, naphtha and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) remain the Achilles’ heel of Brazil’s refined products. [Though] fuel oil has fared notably better in 2015. […He accounts that] “when it comes to electricity, in 2015 Brazil had an installed generating capacity of 140.9 gigawatts (GW). Hydroelectricity accounted for 65.1 percent, while fossil fuel sources made up 17.5 percent and biomass 9.5 percent. For electricity generation purposes imports accounted for 5.85 GW (4 percent) of that amount. Wind and solar power have been increasingly used in the country and both sources have accounted for 5.4 percent of the total (the vast majority of it being wind power). […And] the United States and China have been the biggest importers of Brazilian oil […whereas] the US, Algeria, the Netherlands and Kuwait were the largest suppliers of Brazilian refined products as of 2015.”[35]

Lira critiques Brazil’s unsecured domestic hydrocarbon supply since the country is relegated to producing low-grade oil, cannot process some of its heavy oil and is not able to keep up with tapping the largess of its new oil reserves. He does seem to applaud Brazil’s “prominence in biofuel production and consumption since the 1970s with ethanol (mostly from sugarcane) and biodiesel (from animal fat and vegetables). The promotion of ethanol use in the country gained momentum in the 1970s, partly due to the oil shocks and partly due to the low prices of sugar in that period, which led farmers and the government to redirect a large part of sugarcane’s end-use toward energy production. The production of both sugarcane and ethanol has generally increased since the 1980s. Biodiesel came at a later stage, being formally introduced in the country’s energy matrix in 2005. The purported aim was to increase the country’s energy independence and to boost cleaner production and domestic management of fuel refineries. From 2005 to 2015, the country increased its production at a fast rate.”[36]

Lira begins to uncover the importance and influence of Brazil’s environmentally inclined politics on its national oil company (NOC), Petróleo Brasileiro S.A. (Petrobras), when he concedes that as it relates to “the O&G sector within the larger energy industry in Brazil, it tends to be politically more contentious than, for example, hydroelectricity, solar power and wind power. This is a result of the country’s strong politicization of [exploration and production (E&P)] operations throughout its history, bringing along elements of nationalism, on the one hand, and free market efficiency, on the other, which may be an oversimplification of the state of affairs of E&P in the country. Brazil has responded to global geopolitical shifts in energy relations in the past, particularly the oil crises of the 1970s. It is, therefore, not immune to international shortages of O&G, particularly, and it has, at many times, sought energy independence by developing national industries with a focus on biofuels, for example. […] Overall, as an emerging economy, but still underdeveloped in many areas – not least in the institutional control and supervision of E&P activities – Brazil has not set in place a consistent national-level set of priorities on how O&G resources are to be managed.”[37] According to Lira, the problem that Brazil faced in 2015 is that it could not fulfill its domestic energy needs without further developing its abundant energy resources.

Estimates from the US Energy Information Administration (US EIA) report that as of 2020 and since 2015, Brazil’s oil production has increased by 600 thousand barrels of crude a day. However, in 2020 each day Brazil is processing 1.13 thousand fewer barrels of crude into finished products since 2015.[38] In 2014, Brazil’s “Ministry of Mines and Energy (MME) planned that 30 new large hydropower plants with a total capacity of 30,332 MW should enter into operation until 2023. 91% of this planned capacity is located in the Amazon, and three plants account for 71% of it: Belo Monte (11.000 MW), São Luiz do Tapajós (8.040 MW) and Jatobá (2.338 MW)”.[39] Brazil certainly seems to be trying to keep up with its demand and as recently as December 2021, the EIA reported that Brazil was the only South American country to increase its crude oil production in 2020, year over year.[40] But in 2019 the EIA did estimate that Brazil consumed .539 quadrillion BTUs of coal that it did not produce domestically and consumed .364 quadrillion BTUs of natural gas that it did not produce domestically.[41] Lira’s analysis still holds but if Brazil needs to build more energy generation, it should do so responsibly. In December 2020 Brazil’s Ministry of Mines and Energy published a 2050 National Energy Plan that defends its continued increase in hydroelectric energy production since it “provides high flexibility for the operation of the Brazilian Interconnected System (BIS), allowing a more efficient use of the available renewable resources and reducing the need of fossil fuel plants, that are more expensive, and emit greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.”[42] Hydropower expansion planning in Brazil is what I. Raupp and F. Costa reported in an article that focuses on how to exemplify the applicability and consideration of a new index to choose the most environmentally-appropriate river basin location for a new hydro energy project.

62% of Brazil’s hydroelectric potential has been realized, and the remaining suitable river systems are “concentrated in northern Brazil, characterized by environmentally relevant areas, rich biodiversity, and the presence of indigenous people.”[43] The importance of protecting these areas to mitigate climate change can’t be understated. Though most of the “tropical deforestation [contributing to] about 20% of annual global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [does not come from building more energy generation,] reducing it [as much as possible] will be necessary to avoid [more] dangerous climate change. China and the US are the world’s number one and two [GHG] emitters, but numbers three and four are Indonesia and Brazil, with ~80% and ~70% of their emissions respectively from deforestation.”[44] In Brazil and elsewhere “until 1997, the decision to select the best [hydroelectric dam location] considered only economic-energy efficiency. […] From the 1980s, as environmental awareness increased, environmental and social variables were incorporated into decision-making, resulting in the increasing use of multi-criteria approaches in the 1990s. Since then, models have been proposed to effectively incorporate environmental criteria and sustainability as a prerequisite, analysing the trade-offs between technical, economic, and environmental concerns, including greenhouse gas emissions, water and carbon footprints, and also portfolio investment risk.”[45]

These measures have been part of the evolution of the hydropower inventory studies effort to produce a more sustainable electrical system. The hydropower inventory studies “are carried out by the body responsible for planning Brazil’s electricity sector, the Energy Research Company (EPE) […and incorporated] into the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and Environmental Impact Assessment Report (RIMA) for each project, which are the requirements for obtaining the Preliminary Environmental License from environmental agencies.” Raupp notes that in 2007 the latest version of the hydropower inventory manual focused on three criteria: cost-energy benefit, negative socio-environmental impact, and positive socio-environmental impact related to new hydroelectric power plants. Raupp’s paper developed, analyzed, and compared alternative methods in conducting hydropower inventory studies with a stronger socio-environmental conservation bias to protect against negative impacts on the indigenous people and ecosystems surrounding locations of future hydropower plants. A review of the engineering-focused methodology Raupp undertook is beyond the scope of this paper. He however concludes that the “impacts [of concern] are already strongly considered in the decision-making of inventory studies. […Their] evaluation and quantification in the inventory are very comprehensive and already encompasses all the relevant impacts to be considered at this planning stage.” Unfortunately selecting an optimal location for a hydroelectric dam is still not without political conflict. A complete stakeholder analysis of the conflicts resulting from Brazil’s climate change cognizant coordinated policy strategy is not within the scope of this paper.

However, in the case of the São Luiz do Tapajós (SLT) hydroelectric dam project in Brazil, announced in 2014 by the MME, a study of the inherent conflicts between the stakeholders resulting from the development of any dam in this region has been very well structured into a set of tables, charts, and graphs that appropriately communicate an essential understanding of the conflict. These have been briefly presented to acknowledge the importance of addressing and resolving these politically unintended consequences of the decisions inherent to the Brazilian government energy development plans. It is clear from the process described as part of the hydropower inventory study that the following set of conflicts could have been anticipated and that the negatively affected parties’ damages could be ameliorated or compensated appropriately.[46]

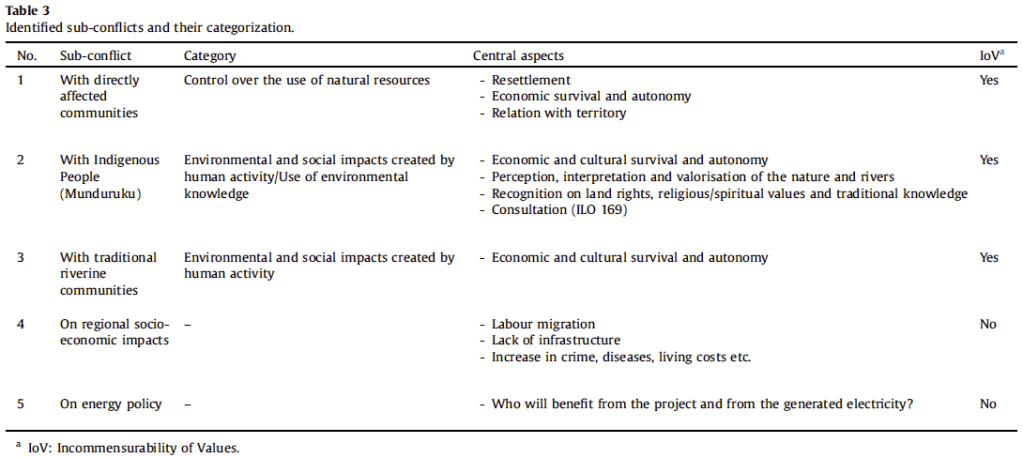

As represented, the two realms “underlying conflict causes” and “conflict treatment” of socio-environmental conflicts have been defined in the following chart.

The following table identifies the socio-environmental conflicts in greater detail.

The complex dynamics of the conflict are well juxtaposed and offer an understanding of the origin of the conflict: the MME’s energy plans; the direction of the parties affected by the plan: going from the lower right to the upper left corner of the chart; and the segments of those presumed to benefit and or have a positive/negative opinion.

The following chart structures in greater detail the results of a set of interviews of stakeholders. Important factors which define these stakeholders “was made based on the review of secondary sources (journalistic and academic articles, the Environmental Impact Assessment and press releases). Subsequently, public representatives of the defined stakeholder groups were selected as interviewees. An interview form was developed in order to cover conflict issues which were found in the literature review. Eleven interviews were conducted during the study. In general, the stakeholder groups opposing the project were more willing to conduct an interview. The planning consortium did not answer the interview questions but issued a statement, highlighting that they are responsible for the viability studies but not (necessarily) for the construction of the plant. Individual companies sought for an interview did not answer.”[47]

Hess concludes, “the complexity of the socio-environmental conflicts originated by the SLT hydropower project, were aggravated by the presence of traditional populations, implying clashes over productive systems, and by the fact that the project does not reflect the endogenous development of the area but is implemented from outside. […] This kind of development inducement is coherent with the past decades of policies aimed at the Amazon, and SLT and other hydropower can be understood as a continuation of the cycle of mega-projects and extractivism, as their energy production is primarily destined to be exported to other regions of Brazil or, as some stakeholder representatives suggest, to large mining projects. […] Its complexity and the power disequilibrium make negotiations without mediation highly unlikely to be successful. […] The current conflict treatment strategy followed by the state and the involved companies, relying on compensation as its central element, falls therefore short for two reasons: First, in a project of the size of SLT, it is unlikely that all negative impacts can be compensated, at least without casting doubt on its profitability. And second, compensation as such is not able to account for the needs at stake. […] The dispute over energy policy and the recognition of the economic, cultural and spiritual rights of traditional populations are central aspects.”[48]

According to Hess, the “solution must be sought, instead, looking at the underlying conflict causes. Here, the dispute over energy policy and the recognition of the economic, cultural and spiritual rights of traditional populations are central aspects. There is no minimal consensus on the energy policy between the proponents and the opponents of the project. For the latter, the current energy policy serves the interest of economic and political elites, whereas the local population suffers the impacts. This issue is therefore about a structural, unequal distribution of benefits and impacts related to energy production in Brazil. The analysis of the historic context in the Amazon validates the worries of the opponents. As long as the government and the involved companies cannot convincingly argue that their energy policy has substantially changed and aims now at a fair distribution of benefits and impacts, negotiations and/ or mediations of the conflicts within the project remain necessarily superficial.”[49] This begins to explain the Brazilian government’s conundrum as they pursue “Order and Progress”. Brazil has demonstrated a consistent predisposition toward developing as environmentally-inclined industrial strategy as their specific circumstances have allowed. As Lira has contended, they could become an international hydrocarbon superpower but instead have sought to develop environmentally friendly approaches to meeting their needs, like biofuel that replaces the need for oil and gas. This highlights the importance of understanding a different aspect of Brazil’s climate change-related system of public policies: its transportation strategy.

Thus far the analysis of the different international, national, and regional Brazilian systems have culminated into a more complete Brazilian version of industrial policy. Historically speaking, the beginning of this industrial policy predated the oil crisis of the 1970s, but it was then that Brazil’s civil-military dictatorship deviated from the response that countries like it, the BRICS, took to develop. Part of Brazil’s nationalistic response at the time included establishing the government departments and state-owned companies like Petrobras that would eventually guide them on this energy development path. These departments are not just technocratic organizations that respond only to the country’s place in the current world order, in the case of Brazil, they are also a direct political reflection of the country’s zeitgeist.

“The years preceding the creation of Petrobras witnessed the popular movement O Petróleo é nosso (‘The Petroleum is Ours’), which defended strictly national control of E&P. With the creation of Petrobras, energy resources were, for decades to come, a state priority. The civil-military regime that followed also emphasized projects of hydroelectricity generation (especially the Itaipu Hydroelectric Dam) and the development of nuclear energy and ethanol as fuel alternatives.”[50] It was not until 1997 that the FDI floodgates were opened “during President Fernando Henrique Cardoso’s administration, [that] the New Petroleum Law eliminated [the] state monopoly on oil exploration and, from then on, other companies were allowed to operate from well to wheel. The concession regime – whereby the state would grant E&P rights to winning companies after a bidding process – became the norm for non-state activities related to oil, natural gas and their transportation. This new model allowed international oil companies (IOCs) to operate more freely in Brazil, either working alone or having Petrobras as a partner.”[51] The resulting Production Sharing Agreement Law was enforced in 2010,[52] and since 2011 Brazil’s daily petroleum production has grown more quickly than that of its BRICS peers.

Thus, the energy-related FDI that Brazil’s domestic energy market has attracted to satisfy its surging demand is not the type of non-polluting FDI Ahmad recommends to deter against further socio-environmental degradation. But it is only one aspect of a set of energy regulatory agencies and NOCs that form boundary organizations that have directed Brazil onto a greener developmental path. Brazil’s early lead on biofuels (including biodiesel) has grown that source of energy to a daily thousand-barrel output of 640.8 Mb/d and globally places it second to only the US (1141.7 Mb/d).[53] While electric vehicles may be the future of the developed world’s ground transportation needs, for some time to come the rest of the world might still need a petroleum replacement that can be used in internal combustion engines that will remain on the road for decades into the 21st century[54]. Mele and Usman’s research to model the sequence of stages of Brazil’s economic growth demonstrates that growing their ecological footprint proceeds greater levels of democracy, and is followed by stronger globalization and eventually results in economic growth. A deeper look into Brazil’s historical growth pattern uncovers that even though its growth begins with an ecological impact, the latest measurements of their per capita carbon footprint (2018) is 2.01 tons, much smaller than most other BRICS: China (7.3 tons), South Africa (7.3 tons), and Russia (11.16 tons). While Brazil’s 2018 per capita carbon footprint is 14.1% higher than India’s (1.76), Brazil’s 2018 per capita GDP (9.1K USD) is 358% larger than India’s (2K USD), and 31% higher than South Africa’s (7K USD).[55] GDP per capita and GHG per capita are two cardinal comparative statistics that will define the success of a country for the rest of the 21st century. While Brazil may become a net oil-exporting country in the near future, the reality of climate change now more than ever may embolden its political elite to look back at its success, learn from the less socio-environmentally equitable aspects of its development and continue a course that may lead the rest of world to a better state for the climate and future welfare of its people.

[1] Conférence des Nations Unies sur le commerce et le développement, ed. 2010. The Financial and Economic Crisis of 2008-2009 and Developing Countries. New York: United Nations.

[2] Milhorance, Carolina, Marcel Bursztyn, and Eric Sabourin. 2020. “From Policy Mix to Policy Networks: Assessing Climate and Land Use Policy Interactions in Mato Grosso, Brazil.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 22 (3): 381–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1740658.

[3] Aklin, Michaël, Patrick Bayer, S. P. Harish, and Johannes Urpelainen. 2013. “Understanding Environmental Policy Preferences: New Evidence from Brazil.” Ecological Economics 94 (October): 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.05.012.

[4] Aklin (35)

[5] “Global Energy Architecture Performance Index 2014 – Reports – World Economic Forum.” n.d. Accessed December 15, 2021. http://reports.weforum.org/global-energy-architecture-performance-index-2014/brics-analysis-of-eapi-performance/?doing wp cron=1639508347.0354568958282470703125.

[6] “International – U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).” n.d. Accessed December 15, 2021. https://www.eia.gov/international/data/world/total-energy/more-total-energy-data.

[7] https://pubs-rsc-org.libproxy.berkeley.edu/en/content/articlepdf/2015/ee/c5ee00888c

[8] Nunes, Felipe, Raoni Rajão, and Britaldo Soares-Filho. 2016. “Boundary Work in Climate Policy Making in Brazil: Reflections from the Frontlines of the Science-Policy Interface.” Environmental Science & Policy 59 (May): 85–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2016.02.009. (89)

[9] The New York Times. 2008. “Brazil Official Cites Giant Oil-Field Discovery,” April 14, 2008, sec. Business. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/14/business/worldbusiness/14iht-14oil.11971599.html.

[10] “International – U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).” n.d. Accessed December 15, 2021. https://www.eia.gov/international/data/world/total-energy/annual-petroleum-and-other-liquids-production

[11] “BRICS: Balancing Economic Growth and Environmental Sustainability.” n.d. Global Energy Architecture Performance Index 2014 (blog). Accessed December 18, 2021. http://wef.ch/1sSEzQl.

12 “BRICS: Balancing Economic Growth and Environmental Sustainability.” n.d. Global Energy Architecture Performance Index 2014 (blog). Accessed December 18, 2021. http://wef.ch/1sSEzQl.

[13] “How a Dam Building Boom Is Transforming the Brazilian Amazon.” n.d. Yale E360. Accessed December 18, 2021. https://e360.yale.edu/features/how-a-dam-building-boom-is-transforming-the-brazilian-amazon.

[14] Ferreira, J., L. E. O. C. Aragão, J. Barlow, P. Barreto, E. Berenguer, M. Bustamante, T. A. Gardner, et al. 2014. “Brazil’s Environmental Leadership at Risk.” Science 346 (6210): 706–7. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1260194.

[15] Hastings, Jesse. 2011. “International Environmental NGOs and Conservation Science and Policy: A Case from Brazil.” Coastal Management 39 (3): 317–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2011.566125.

[16] Hastings (318)

[17] Milhorance, Carolina, Marcel Bursztyn, and Eric Sabourin. 2020. “From Policy Mix to Policy Networks: Assessing Climate and Land Use Policy Interactions in Mato Grosso, Brazil.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 22 (3): 381–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1740658. (381)

[18]Milhorance (388)

[19] Milhorance (392)

[20] U.S. Department of State. 2020 Investment Climate Statements: Brazil.

[21] Umer Jeelanie Banday, Saravanan Murugan & Javeria Maryam (2021) Foreign direct investment, trade openness and economic growth in BRICS countries: evidences from panel data, Transnational Corporations Review, 13:2, 211-221, DOI: 10.1080/19186444.2020.1851162

[22] Ahmad, Mahmood, and Muhammad Yousaf Raza. 2020. “Role of Public-Private Partnerships Investment in Energy and Technological Innovations in Driving Climate Change: Evidence from Brazil.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research International 27 (24): 30638–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-09307-w (30646)

[23] (Ahmad) (30639)

[24] (Ahmad) (30639)

[25] (Ahmad) (30639)

[26] Mele, Marco. 2019. “Economic Growth and Energy Consumption in Brazil: Cointegration and Causality Analysis.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research 26 (29): 30069–75.

[27] Mele (30075).

[28] Mele (30075)

[29] “How Brazil Can Optimize Its Cost of Energy | McKinsey.” n.d. Accessed December 17, 2021. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/electric-power-and-natural-gas/our-insights/how-brazil-can-optimize-its-cost-of-energy.

[30] Usman, Ojonugwa, Iormom Bruce Iortile, and George Nwokike Ike. 2020. “Enhancing Sustainable Electricity Consumption in a Large Ecological Reserve-Based Country: The Role of Democracy, Ecological Footprint, Economic Growth, and Globalisation in Brazil.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research International 27 (12): 13370–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-07815-3.

[31] Usman, Ojonugwa, Iormom Bruce Iortile, and George Nwokike Ike. 2020. “Enhancing Sustainable Electricity Consumption in a Large Ecological Reserve-Based Country: The Role of Democracy, Ecological Footprint, Economic Growth, and Globalisation in Brazil.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research International 27 (12): 13370–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-07815-3.

[32] Usman (13380)

[33] Flavio Lira. 2018. “Between Global Aspirations and Domestic Imperatives: The Case of Brazil : Handbook of the International Political Economy of Energy and Natural Resources.” n.d. https://www.elgaronline.com/view/edcoll/9781783475629/9781783475629.00035.xml.

[34] Lira (356)

[35] Lira (357)

[36] Lira (361)

[37] Lira (366)

[38] “International – U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).” n.d. Accessed December 15, 2021. https://www.eia.gov/international/data/world/total-energy/more-total-energy-data.

[39] Hess, Christoph Ernst Emil, and Eva Fenrich. 2017. “Socio-Environmental Conflicts on Hydropower: The São Luiz Do Tapajós Project in Brazil.” Environmental Science & Policy 73 (July): 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.03.005.

[40] “Brazil Was the Only South American Country to Increase Crude Oil Production in 2020 – Today in Energy – U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).” n.d. Accessed December 17, 2021. https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=50538.

[41] “International – U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).” n.d. Accessed December 15, 2021. https://www.eia.gov/international/data/world/total-energy/more-total-energy-data.

[42] “Plano Nacional de Energia 2050 – Ministério de Minas e Energia.” n.d. Accessed December 17, 2021. http://antigo.mme.gov.br//web/guest/secretarias/planejamento-e-desenvolvimento-energetico/publicacoes/plano-nacional-de-energia-2050.

[43] Raupp, I., and F. Costa. 2021. “Hydropower Expansion Planning in Brazil – Environmental Improvements.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 152 (December): 111623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.111623.

[44] “Measuring Carbon Emissions from Tropical Deforestation: An Overview” n.d. Accessed December 17, 2021. http://antigo.mme.gov.br//web/guest/secretarias/planejamento-e-desenvolvimento-energetico/publicacoes/plano-nacional-de-energia-2050.

[45] Raupp (3)

[46] Hess, Christoph Ernst Emil, and Eva Fenrich. 2017. “Socio-Environmental Conflicts on Hydropower: The São Luiz Do Tapajós Project in Brazil.” Environmental Science & Policy 73 (July): 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.03.005.

[47] Hess (5)

[48] Hess (27)

[49] Hess (27)

[50] Lira (363)

[51] Lira (364)

[52] Almada, Laís & Parente, Virginia. (2018). Oil & Gas Industry In Brazil: A Brief History And Legal Framework. Panorama Of Brazilian Law. 1. 223-252. 10.17768/pbl.v1i1.34368.

[53] “International – U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).” n.d. Accessed December 18, 2021. https://www.eia.gov/international/data/world/biofuels/more-biofuels-data.

[54] “IJER Editorial: The Future of the Internal Combustion Engine – R D Reitz, H Ogawa, R Payri, T Fansler, S Kokjohn, Y Moriyoshi, AK Agarwal, D Arcoumanis, D Assanis, C Bae, K Boulouchos, M Canakci, S Curran, I Denbratt, M Gavaises, M Guenthner, C Hasse, Z Huang, T Ishiyama, B Johansson, TV Johnson, G Kalghatgi, M Koike, SC Kong, A Leipertz, P Miles, R Novella, A Onorati, M Richter, S Shuai, D Siebers, W Su, M Trujillo, N Uchida, B M Vaglieco, RM Wagner, H Zhao, 2020.” n.d. Accessed December 18, 2021. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1468087419877990.

[55] “CO2 Emissions (Kt) – Brazil, China, India, Russian Federation | Data.” n.d. Accessed December 18, 2021. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.ATM.CO2E.KT?cid=GPD_31&locations=BR-CN-IN-RU.